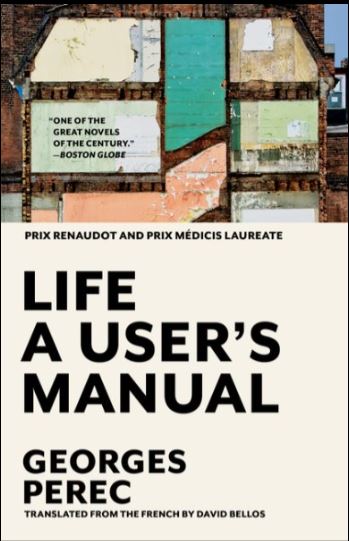

I read Georges Perec’s Life: A User’s Manual when I was a master’s student in physics. At the time, I was toiling through books and lectures on classical and quantum mechanics—essentially, working for a degree. The Lagrangian and Hamiltonian equations, particle theories, their graduation to quantum physics, and further into Schrödinger and Heisenberg’s formulations, all passed by in a haze.

I was grappling with the concept of constraints in Lagrangian mechanics when I opened Perec’s preface. In it, he forewarned the reader about the games and devices he had woven into his novel. Although he wrote the book to be eminently readable, he made no bones about the underlying rigor of its construction: the sequence of chapters follows the algorithm of a chess game; jigsaw puzzles, crosswords, and probabilistic formulas organize the literary elements—objects, characters, situations, allusions, and quotations—into a deliberate order; even the indexing of its ninety-nine chapters is modeled after Dewey. It was the mind of an architect at work—focused, meticulous, and simultaneously non-committal about the grandeur of the project, stoic about its futility, and dispassionately observant of life’s intricate goings-on.

Lagrange essentially said that imposing constraints on a system is another way of stating that forces are present in the problem which cannot be specified directly, but whose effects on motion are known. Perec took this principle into literature—adopting constraints as an empirical approach to writing and, by extension, to reading.

Perec was part of the Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (Oulipo) group, devoted to the study and invention of literary forms. Under the leadership of Raymond Queneau and François Le Lionnais, the Oulipo worked—and still works—to identify and revive neglected forms, while also devising new ones based on rigorous formal constraints. One member famously defined the group, tongue firmly in cheek: “Oulipians: Rats who must build the labyrinth from which they propose to escape.” Perec found a home here, among writers like Jacques Roubaud, Harry Mathews, Italo Calvino, and Marcel Bénabou.

Life: A User’s Manual tells the story of a ten-story building at the fictional 11, rue Simon-Crubellier in Paris, meticulously describing its interior and the lives of its residents—179 stories in all. Their order is determined by a famous chess problem: visiting every square on a board using only the knight’s move. Once the constraints are set, Perec emerges as anything but a cold formalist—his affection for the characters and their idiosyncrasies is unmistakable. The stories stir wonder, laughter, and reflection, as they reinvent genres—romance, drama, detective tale, adventure, murder mystery—through restaurateurs, mediums, cyclists, antique dealers, and pious widows.

Some examples:

– A trapeze artist’s swansong at the circus—an impossible feat that ends in his death.

– An archaeologist on the Nile trying to rescue a German girl from a harem.

– A judge’s wife whose thrilling thefts lead to hard labor, ending as a bag lady on a park bench.

– A murder mystery in which the protagonist adopts the Monte Carlo theory of probability to find his wife’s and daughter’s killer—only to narrowly miss encountering him.

– A prophecy that shadows generations of a tragedy-stricken family, glimpsed only in a brief visit to an empty apartment.

These stories leave little doubt about Perec’s storytelling gift. Beneath them all runs a subtle negotiation between writer and reader, with the big picture always in the backdrop. That is where Perec introduces his central figures: Bartlebooth, the millionaire maverick painter; Gaspard Winckler, his assistant; and Valène, the concierge who narrates this intricate web of stories.

Bartlebooth’s project is monumental: over twenty years, he will travel the world painting 500 watercolors of different harbors. Every other week, a painting is sent to Winckler, who mounts it on wood and cuts it into a 750-piece jigsaw puzzle. Once Bartlebooth returns, he will spend another twenty years reassembling the puzzles, then return each to its original harbor, where it will be washed clean, leaving a blank sheet—the beginning and end coinciding. But things do not go as planned.

To avenge twenty years of “pointless” work, Winckler begins making the puzzles increasingly difficult. Almost blind, Bartlebooth dies while attempting the 439th puzzle. Perec’s final paragraph captures the irony:

“It is the twenty-third of June nineteen seventy-five, and it is eight o’clock in the evening. Seated at his jigsaw puzzle, Bartlebooth has just died. On the tablecloth, somewhere in the crepuscular sky of the four hundred and thirty-ninth puzzle, the black hole of the sole piece not yet filled in has the almost perfect shape of an X. But the ironic thing, which could have been foreseen long ago, is that the piece the dead man holds between his fingers is shaped like a W.”

Winckler, dead two years earlier, has triumphed—but it is a meaningless triumph.

In a single paragraph, Perec captures the grand project of life, the inherent meaninglessness of human effort, and the role of chance in undoing even the most carefully designed schemes. Our lives are shaped by innumerable constraints—social, ethical, moral, physical, biological—some accepted, some resisted—while the interplay of chaos and order goes mostly unnoticed.

For someone who once wrote a novel entirely without the letter e, and as a leading figure of the Oulipo movement, this feels like a summit. In it, you sense the shadow of Joyce, Borges, Calvino, Flaubert, and Kafka—but also something uniquely Perec’s own.

For now, I have nothing more to say. Go read it—the book belongs to you, my dear reader.

Tag: book-reviews

-

Life A User’s Manual

-

The Great Gatsby

F, Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is a short, dense novel. He is not one of my usual choices of writers to pick up and read. But the flair and taut writing had me hooked. His exquisite craft in narrating the Long Island soirees from the Jazz Age where midwesterners came to claim the American dream amid their insecurities about displacement by inferior races, nouveau-riche threatening class barriers and traditional social order, women becoming the co-conspirators to relegate themselves to “beautiful little fools” of their possessors’ social standing – weaving layers of socio-political commentary.

Nick Carraway, the narrator of the story – a mid-westerner presents an empathetic portrayal of Gatsby, who, in turn, was ingratiating himself into Nick’s life to get close to Daisy Buchanan, Gatsby’s long-lost love. He takes time to shed light on the main characters – Tom Buchanan, the rich and imperious former polo player and Yale alumnus, whom Daisy reluctantly married when Gatsby, son of a poor Lutheran farmer, left town to war with the world and earn enough to marry her. Daisy Buchanan is Nick’s cousin, who grew up in a wealthy family, is a victim and sustainer of the class system of old money as she tolerated Tom’s adultery, condoned racist rants, and finally abandoned Gatsby to his fate, notwithstanding her unabashed love and attraction for him.

Gatsby conquered the world with the best of American traditions – bootlegging during the prohibition era, insider trading, and other illegal activities, only to settle down near Nick’s house. He ran parties all night without taking part in them, and used them only as a ruse to get close to Daisy. Having Daisy invited over to Nick’s house, Gatsby asked her to play the piano despite her protests about being out of practice. He was reliving the enchantment he lost five years ago, which Nick observed through the bewilderment on Gatsby’s face when Daisy “tumbled short of his dreams-not through her fault, but because of the colossal vitality of his illusion”. Nick went out of the room, leaving them to be “possessed by intense life”.

Tom punctured Gatsby’s illusion with the help of a private detective and warned Daisy of the source of his wealth. Their confrontation led to tragedy when Daisy, while driving back home, hit Tom’s lover accidentally and ran away. Gatsby tried to protect her as he hid the car in his garage and later kept a night vigil in the garden to see if Daisy was safe in her room with the lights off. Tom, after a while, reveals that he told the heartbroken widower of his lover, Wilson, that the car that killed her belonged to Gatsby. Wilson committed suicide after shooting Gatsby. Nick finally meets Mr. Gatz, Gatsby’s dog-tired father, as they attend the loneliest funeral sans the sounds of Jazz and the flock of humans.

Nick, too, leaves New York, brooding over the old, unknown world, and he thought how Gatsby “picked out the green light from Daisy’s dock”. He didn’t realize that the dream he thought so real in his grasp was already behind him. Fitzgerald finishes with a flourish on our collective American dream etched on the Statue of Liberty:

“Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter – tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther…. And one fine morning……

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”