I read Georges Perec’s Life: A User’s Manual when I was a master’s student in physics. At the time, I was toiling through books and lectures on classical and quantum mechanics—essentially, working for a degree. The Lagrangian and Hamiltonian equations, particle theories, their graduation to quantum physics, and further into Schrödinger and Heisenberg’s formulations, all passed by in a haze.

I was grappling with the concept of constraints in Lagrangian mechanics when I opened Perec’s preface. In it, he forewarned the reader about the games and devices he had woven into his novel. Although he wrote the book to be eminently readable, he made no bones about the underlying rigor of its construction: the sequence of chapters follows the algorithm of a chess game; jigsaw puzzles, crosswords, and probabilistic formulas organize the literary elements—objects, characters, situations, allusions, and quotations—into a deliberate order; even the indexing of its ninety-nine chapters is modeled after Dewey. It was the mind of an architect at work—focused, meticulous, and simultaneously non-committal about the grandeur of the project, stoic about its futility, and dispassionately observant of life’s intricate goings-on.

Lagrange essentially said that imposing constraints on a system is another way of stating that forces are present in the problem which cannot be specified directly, but whose effects on motion are known. Perec took this principle into literature—adopting constraints as an empirical approach to writing and, by extension, to reading.

Perec was part of the Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (Oulipo) group, devoted to the study and invention of literary forms. Under the leadership of Raymond Queneau and François Le Lionnais, the Oulipo worked—and still works—to identify and revive neglected forms, while also devising new ones based on rigorous formal constraints. One member famously defined the group, tongue firmly in cheek: “Oulipians: Rats who must build the labyrinth from which they propose to escape.” Perec found a home here, among writers like Jacques Roubaud, Harry Mathews, Italo Calvino, and Marcel Bénabou.

Life: A User’s Manual tells the story of a ten-story building at the fictional 11, rue Simon-Crubellier in Paris, meticulously describing its interior and the lives of its residents—179 stories in all. Their order is determined by a famous chess problem: visiting every square on a board using only the knight’s move. Once the constraints are set, Perec emerges as anything but a cold formalist—his affection for the characters and their idiosyncrasies is unmistakable. The stories stir wonder, laughter, and reflection, as they reinvent genres—romance, drama, detective tale, adventure, murder mystery—through restaurateurs, mediums, cyclists, antique dealers, and pious widows.

Some examples:

– A trapeze artist’s swansong at the circus—an impossible feat that ends in his death.

– An archaeologist on the Nile trying to rescue a German girl from a harem.

– A judge’s wife whose thrilling thefts lead to hard labor, ending as a bag lady on a park bench.

– A murder mystery in which the protagonist adopts the Monte Carlo theory of probability to find his wife’s and daughter’s killer—only to narrowly miss encountering him.

– A prophecy that shadows generations of a tragedy-stricken family, glimpsed only in a brief visit to an empty apartment.

These stories leave little doubt about Perec’s storytelling gift. Beneath them all runs a subtle negotiation between writer and reader, with the big picture always in the backdrop. That is where Perec introduces his central figures: Bartlebooth, the millionaire maverick painter; Gaspard Winckler, his assistant; and Valène, the concierge who narrates this intricate web of stories.

Bartlebooth’s project is monumental: over twenty years, he will travel the world painting 500 watercolors of different harbors. Every other week, a painting is sent to Winckler, who mounts it on wood and cuts it into a 750-piece jigsaw puzzle. Once Bartlebooth returns, he will spend another twenty years reassembling the puzzles, then return each to its original harbor, where it will be washed clean, leaving a blank sheet—the beginning and end coinciding. But things do not go as planned.

To avenge twenty years of “pointless” work, Winckler begins making the puzzles increasingly difficult. Almost blind, Bartlebooth dies while attempting the 439th puzzle. Perec’s final paragraph captures the irony:

“It is the twenty-third of June nineteen seventy-five, and it is eight o’clock in the evening. Seated at his jigsaw puzzle, Bartlebooth has just died. On the tablecloth, somewhere in the crepuscular sky of the four hundred and thirty-ninth puzzle, the black hole of the sole piece not yet filled in has the almost perfect shape of an X. But the ironic thing, which could have been foreseen long ago, is that the piece the dead man holds between his fingers is shaped like a W.”

Winckler, dead two years earlier, has triumphed—but it is a meaningless triumph.

In a single paragraph, Perec captures the grand project of life, the inherent meaninglessness of human effort, and the role of chance in undoing even the most carefully designed schemes. Our lives are shaped by innumerable constraints—social, ethical, moral, physical, biological—some accepted, some resisted—while the interplay of chaos and order goes mostly unnoticed.

For someone who once wrote a novel entirely without the letter e, and as a leading figure of the Oulipo movement, this feels like a summit. In it, you sense the shadow of Joyce, Borges, Calvino, Flaubert, and Kafka—but also something uniquely Perec’s own.

For now, I have nothing more to say. Go read it—the book belongs to you, my dear reader.

Posts

-

Life A User’s Manual

-

Song of seasons

The songs of seasons

May:

The Country road lay like a tamed snake, brown and parched, heaving and teary-eyed. Sunshine raced to distant fields like wildfire and bounced off broken heaps of images. The wasteland subsisted on dried tuber and the wisdom of defiant dry bones of the river bed. The fire sermon was delivered in May.

The ceiling fan in your room is a bit of schizophrenic, besides being old and cranky, and you lie in your bed, etherized; while the vagaries of Summer and memories melted in crimson flames. 1

June:

Monsoon arrived when the dark clouds with lightning streaks broke the skies’ boundary. The air grew dense. It wafted the scent of impregnated soil. Trade winds came and then came meghmalhar. An alaap began in vilambit interval swelled on to madhyam and culminated in an endless dhrut khayaal. A million drops of rain fell on the remains of life on Earth. The puddles, rivulets, streams, rivers, lagoons, and whirlpools flowed, swollen by a mass of turbid waters rushed with impetuous haste towards the seas, felling trees and deluge-struck mortals all around on their banks and washed them to a timeless shore.2

September:

A sudden light shower in the morning, left the yard exhilarated and let it regain composure. The laughter and mirth from the living room grew with sunshine. Today is Onam. There is weightlessness in reunion and barricading time to slip any further. Spring is now and hope is in the moment.

November:

Autumn is too short to pause and ruminate over the blinding beauty of orange evenings and golden yellow leaves. And yet one ruminates, invariably. In one of these autumns, Lorca3 moved to New York while it ushered in the great depression. The autumnal marvels of his Granada, its solitary rose breath and its leaves, reflections of pillars and arabesques in the pools, the splashing fountains and the profusion of myrtle and pomegranate – were all estranged, now. The loss of November!

January:

Winter can wreck your senses, nudge them into frigidity, and remind you that you live in a world of morbid nerves, clear and cold as ice. The cold winds blowing across the snowy landscape can bring in the visage of death and a possibility of enlightenment. You may even gain the courage to glance at the white emptiness that lay beyond the limits of your eyes and the moonbeam’s icy glitter. The winter in your sense organs would tell you that you have always been in a snowy country, alone and unable to speak.4

Note: The color and sound of the seasons have been inspired by the following writers.

1. Thomas Stearns Eliot (The Wasteland) 2. Mahakavi Kalidasan (Ritusamharam) 3. Federico Garcia Lorca (Poems in Newyork) 4. Yasunari Kawabata (Snow Country)

-

Hope Springs Eternal

My aunt’s husband left the city of Kochi (Kerala, India) after retiring as a Deputy Revenue Officer. He relocated his wife, and children, except for the oldest daughter finishing college, to Chelakkara in the early seventies, a sparsely populated boondock northwest of Thrissur. After a day-long journey by bus, I had to walk for miles on a rough, winding road flanked by undulating paddy fields on either side until it became an unpaved but equally wide rugged rural pathway, leading to the gate bearing their family name inscribed.

The house stood in the middle of several acres of land with a bamboo fence. The yard was filled with various fruit trees – many mangoes, jackfruit, guava, gooseberry, cashew apples, and Sapodillas. I was told my uncle even attempted farming paddy once. The original owner of the land was his neighbor. The house also had a cavernous well with nothing but rock at the bottom which my cousin wistfully described as a money pit where his father threw away a fortune over several years hoping for a spring. Now it was just a reservoir for rainwater that dries up in the summer for snakes to snuggle in the damp and shade.

The house was spacious with a room full of antique cupboards where I found a treasure of his collection of books and audio cassettes. In a chest, I found an official invitation to the first show in Shenoy’s theater in Kochi for its grand opening which someone kept as a souvenir. Uncle had diaries with quotations from and annotations on Malayalam poets, mostly by G. Shankara Kuruppu and Vallathol. It also had notes and tips on farming. I realized the books on Physics and World literature belonged to his brother who died young when he was a lecturer at Brennen College. The complete collection of Yesudas’s Hindi Songs too was his legacy. I never met him. I saw my uncle only twice, of which the second meeting was when I traveled for almost all day in several buses with my parents for his funeral. He visited us a few months earlier to seek my parent’s help to dissuade his younger son from marrying a young girl he met near the dorm, having decided to drop out of college.

I observed none of my cousins were interested in the books or farming. No one else studied beyond High school or basic trade school while their cousins in Kochi were known for academic excellence including post-doctoral degrees. The older daughter got a job in Government, married, and continued to live in Kochi. They sold the property by the end of 1999 back to the neighbor for a price. Until her last, my Aunt, who retired as a teacher ages ago, lived with the younger son who became a primary school teacher in a small town closer to Kochi. He divorced his first love and is separated from second wife. The other children too found their place now closer to Kochi even though they are still a few hours away.

I remember watching a French film starring Gerard Depardieu – Jean De Florette (1986). Depardieu played the character of Jean, the Tax Collector and son of Florette who returns with his wife and daughter to the village to claim the land he inherited from his mother to begin the life of a farmer. Ugolin, his neighbor and local farmer who fought with Jean’s uncle earlier for not selling the land, realized that Jean too did not intend to sell. Despite all the efforts to make Jean’s life hell, Ugolin couldn’t make Jean sell his house. He along with an accomplice blocked the spring that was the only source of water forcing Jean to begin digging a well to collect rainwater at least as long as that lasts. Unfortunately while trying to blast open the well, Jean gets hit by a rock and dies. Jean’s distraught and orphaned family sells the house to Ugolin and leaves the village. Soon after, Ugolin unblocks the spring and begins to make a good profit.

-

The Great Gatsby

F, Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is a short, dense novel. He is not one of my usual choices of writers to pick up and read. But the flair and taut writing had me hooked. His exquisite craft in narrating the Long Island soirees from the Jazz Age where midwesterners came to claim the American dream amid their insecurities about displacement by inferior races, nouveau-riche threatening class barriers and traditional social order, women becoming the co-conspirators to relegate themselves to “beautiful little fools” of their possessors’ social standing – weaving layers of socio-political commentary.

Nick Carraway, the narrator of the story – a mid-westerner presents an empathetic portrayal of Gatsby, who, in turn, was ingratiating himself into Nick’s life to get close to Daisy Buchanan, Gatsby’s long-lost love. He takes time to shed light on the main characters – Tom Buchanan, the rich and imperious former polo player and Yale alumnus, whom Daisy reluctantly married when Gatsby, son of a poor Lutheran farmer, left town to war with the world and earn enough to marry her. Daisy Buchanan is Nick’s cousin, who grew up in a wealthy family, is a victim and sustainer of the class system of old money as she tolerated Tom’s adultery, condoned racist rants, and finally abandoned Gatsby to his fate, notwithstanding her unabashed love and attraction for him.

Gatsby conquered the world with the best of American traditions – bootlegging during the prohibition era, insider trading, and other illegal activities, only to settle down near Nick’s house. He ran parties all night without taking part in them, and used them only as a ruse to get close to Daisy. Having Daisy invited over to Nick’s house, Gatsby asked her to play the piano despite her protests about being out of practice. He was reliving the enchantment he lost five years ago, which Nick observed through the bewilderment on Gatsby’s face when Daisy “tumbled short of his dreams-not through her fault, but because of the colossal vitality of his illusion”. Nick went out of the room, leaving them to be “possessed by intense life”.

Tom punctured Gatsby’s illusion with the help of a private detective and warned Daisy of the source of his wealth. Their confrontation led to tragedy when Daisy, while driving back home, hit Tom’s lover accidentally and ran away. Gatsby tried to protect her as he hid the car in his garage and later kept a night vigil in the garden to see if Daisy was safe in her room with the lights off. Tom, after a while, reveals that he told the heartbroken widower of his lover, Wilson, that the car that killed her belonged to Gatsby. Wilson committed suicide after shooting Gatsby. Nick finally meets Mr. Gatz, Gatsby’s dog-tired father, as they attend the loneliest funeral sans the sounds of Jazz and the flock of humans.

Nick, too, leaves New York, brooding over the old, unknown world, and he thought how Gatsby “picked out the green light from Daisy’s dock”. He didn’t realize that the dream he thought so real in his grasp was already behind him. Fitzgerald finishes with a flourish on our collective American dream etched on the Statue of Liberty:

“Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter – tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther…. And one fine morning……

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

-

Crowd, Power and Space

Crowd, Power and Spaces

Israel is up against a triple crowd surging in three-dimensional space doubling down on its maximalist demands to find some ways to vanish from the center of their universe —morally, militarily, and symbolically. It’s not merely a military conflict; it’s a struggle over legitimacy, truth, and the right to exist as a liberal democracy amid ideological absolutism.

The First Crowd

Having raided across the lines of enemy territory, the savage plunderers chosen by the tribal gods exacted untold trauma and brought enough prisoners. They formed the first crowd to do the job of baiting the armed foes coming in with survivors’ guilt and irrational haste to the arena. Physically they have surrounded themselves with concentric circles of prisoners and people from their own tribe.

The Second crowd

Both prisoners and unarmed civilians form the firewall even the cruelest dictator would dream about. They are the crowds of lament. The worse their plight becomes, the enemy’s will to fight worsens. The terrorists wish nothing but the worst inflicted upon them and suffer immeasurably from the fury of retribution. It is indeed heartbreaking to watch death and destruction in the wake of an apocalypse and a densely packed city laid asunder.

The Third crowd

The marching crowds in the world’s cities and schools demanding complete surrender to what they will ask next is possibly the most dangerous of the three. Champions of ideologies – both religious and liberal kind found an intersection in their disdain for democracy and lust for power to close down avenues for dialogue, coexistence, and peace. Their politics of grievance gives them the opportunity to destabilize the world order and hope for another Iran or a resurrection of Soviet Gulags out of the rubble. They believe the union outmaneuvers reason and logic with intentionally loud and prosaic phrases like apartheid, occupation, open prison, etc., while promising that the crowd will overrun the few million Jewish survivors shortly, notwithstanding their deadly weapons of mass destruction. They do not have the patience to listen to the stories from the holocaust.

Three-dimensional space

The terrorists spent their entire fortune building a metro of tunnels under their city of squalor and suffering. They crawl out of the holes to inflict pain on others or draw them into the dark traps of death.

The population living above ground in the ghastly city is held hostage to the regime of terror while being the willing and fertile source to recruit their rank and file.

The sympathizers all over the world occupy spaces in the multiverse of the internet, town squares, the labyrinth of universities, and ghettoes where immigrants import unsolvable animus from the dark ages.

-

Israel and the Baiting Crowd

When mythology becomes ideology and ideology becomes execution, a darker logic takes hold.

The blood-curdling acts of cruelty unleashed on civilians in their homes—targeted killings, hostage-taking, and indiscriminate violence—mark a terrifying regression into primal forms of conflict. These actions, as witnessed in recent Hamas attacks, go far beyond political grievance or tactical warfare. They reflect an ideological totality rooted in an unredeemable vision of the enemy. In such a vision, there is no room for coexistence—only elimination.

Radical Islamic terrorism, such as that espoused by Hamas, draws its fervor from literalist interpretations of religious texts. These scriptures, while diverse and often poetic, are seized upon by extremists to construct closed, absolutist narratives—myths that sanctify violence and demonize the other.

Yuval Harari, in Sapiens, argues that Homo sapiens rose to dominance not through brute strength but through the unique ability to share stories—fictional narratives that enabled mass cooperation. Religion, like law and nationalism, is among the most enduring of these inventions. These stories—what Harari calls “gossip”—bind individuals into communities. But when transformed into dogma and wrapped in divine authority, they can become weapons.

This is the foundation of radical Islamist ideology: where myth becomes command, and faith becomes justification for violence. The enemy is no longer just a political adversary, but a moral and ontological threat whose very existence defiles the sacred narrative. The religious story becomes a call to arms.

The execution of this call finds disturbing resonance in Elias Canetti’s Crowd and Power. Canetti describes the “baiting crowd” as the most ancient and primal form of collective action. It forms around a quickly attainable goal: a victim, clearly marked, defenseless, destined. The crowd moves with single-minded purpose. Each individual strikes a blow, not out of strategy, but out of ritual. The killing is both symbolic and literal—meant to rid the group of its own fear, its own death. Yet paradoxically, after the execution, the crowd disperses, more anxious and fractured than before.

This, then, is the horrifying convergence: Harari’s myth-making meets Canetti’s crowd impulse. The ideology draws legitimacy from scripture, and the crowd, believing in that narrative, acts it out with blood-soaked devotion.

In the ideology of Hamas, we see this pattern laid bare. A theology that lionizes martyrdom and promises divine reward collides with a political fantasy of erasing Israel. The result is a mobilized crowd willing to kill and be killed—not as soldiers, but as believers acting out a sacred script.

What makes this moment more dangerous is the global amplification of this narrative. Despite Hamas’s use of civilians as human shields, its genocidal charter, and its rejection of compromise, there is a rush—in parts of the Islamic world and among segments of the global left—to frame its actions as resistance rather than terror. Israel’s right to self-defense is questioned more than Hamas’s right to exist.

This signals a disturbing moral inversion. Those who slaughter in the name of God are humanized. Those who retaliate to protect civilians are pathologized. The baiting crowd is no longer confined to streets or battlefields. It has gone virtual, networked, and transnational—spurred on by ideology, grievance, and a prophetic sense of historical destiny.

Harari ends Sapiens with a warning: that humanity, having acquired godlike technologies, remains dangerously guided by prehistoric instincts. Unless we interrogate the stories we believe in—how they form, how they justify violence, how they sanctify crowds—we risk returning to the oldest form of brutality: the hunting pack, now cloaked in scripture and broadcast to billions.

-

Atlantis, the lost island of childhood

In the beginning, as far as I can remember, the lush green strip of land was ensconced by the Arabian Sea and a thin river line that was lost into an estuary. A billion species of life thrived in the tiny whirlpools. Sunshine fell on the flowing waters in every fissure. When it rained, the natives who lived in the shanty could see the silver lines of thunder afar and scampered to bring the cows and kids home from the field and the wantons of country roads. The wind wove a symphony across the countless coconut trees that arched over the white and golden sand dunes. Folks called the place – an island, with no name, perhaps to remind the sovereignty of the land that leant over the timeless ebb and flow of the ocean.

I used to visit my grandparents’ house during our summer vacations. We, the boys from the city found our space and deflated the overcrowded time from our senses on the island. The travel included trekking by bus and ferry boats, finally walking more than a mile passing paddy fields and country roads paved with soft red soil and sand until we reach the Riverbend and holler for the ferry as we soak in the wet breeze wiping away the last trace of fatigue.

The folks in the house had to paddle across the river for everything that they ever needed, and every household had its own boats. The nights were dense and we could see each other’s faces in sepia sitting across the kerosene lamps for dinner. Eight siblings and dozens of grandkids thronged the spacious and benevolent home during those unforgettable times. If I close my eyes, I can still see the shimmering torch lights of solitary pedestrians on those rugged paths by the river and fisher folks rowing by.

It must be right after the famine in the forties, my grandfather and his brothers left their misery to follow a dream of a piece of land to call their own. I never asked him to chronicle the events or timeline. They had nothing and everything to fight for. The island was waiting for them to build the Promised Land, and the earth was nubile and feisty. He had plowed his way and unleashed the raw power of farmers and fishermen to build the house, cultivate the land and build boats to fish with a lot of camaraderie with his brothers and natives.

As kids, we spent the summer vacations in exhilaration, playing on top of the piles of coconuts and grains; canoeing up and down streams; gathering around the table where everyone assembles for dinner and woke up with the roar of waves retreating from the back of the house every morning. My grandfather looked like Odysseus who just came home to Ithaca, having done his journey.

I spent a lot of time with him listening to his monologues on movies he watched from the country movie theatre or the quality of carpenters who worked on his boats. He also spoke about the murderous sea storms and fights among fisher folks who haunted the evening taverns with a kind of defiant nonchalance. He was Hemingway’s Santiago who came from the sea with the biggest fish I could ever imagine sculling the boat from the horizon, but he was not weary.

I never asked my grandfather about his journey, rather I was basking in his days of glory. But then things took a different course ever since he folded himself into retirement. My aunts were all married off and had more significant issues in life and kids to gather around, my uncles vanished into the crowds in different parts of India and outside in search of jobs.

Society itself was undergoing the customary changes as always has been. The deluge of foreign money and pomp of Gulf country residents rolled over the spirit of the land. The old house was abandoned and the grandparents were transplanted to the new home built near the highway and surrounded by walls. The rain, the wind, the undulating expanse of coconut trees, and the waves from the ocean were shut out for the rest of their lives.

Grandma died first and Grandfather followed her soon. Even the new house looks so old now, occupied now by one of my uncles. He might probably visit once in a while from Dubai where he found a job. The dilapidated and moth-ridden old house bid the last moments of its existence before it was smashed down, probably to build a concrete warehouse for fertilizers. Now that the island has been named and electrified.

Atlantis, the lost continent is considered to be the source of all Religion, all Science, and all races and civilizations. As we enter the third millennium, the Age of Aquarius its discovery is deemed to cause a major revolution in our view of the world and of both our future and past. I found my Atlantis on that island a while ago when I was a kid. The hearts and minds of the dwellers who built a brave new world over there, though lost, would still speak to you if you listen. That this world can still be mysterious and beautiful if you can spare a moment to grasp.

-

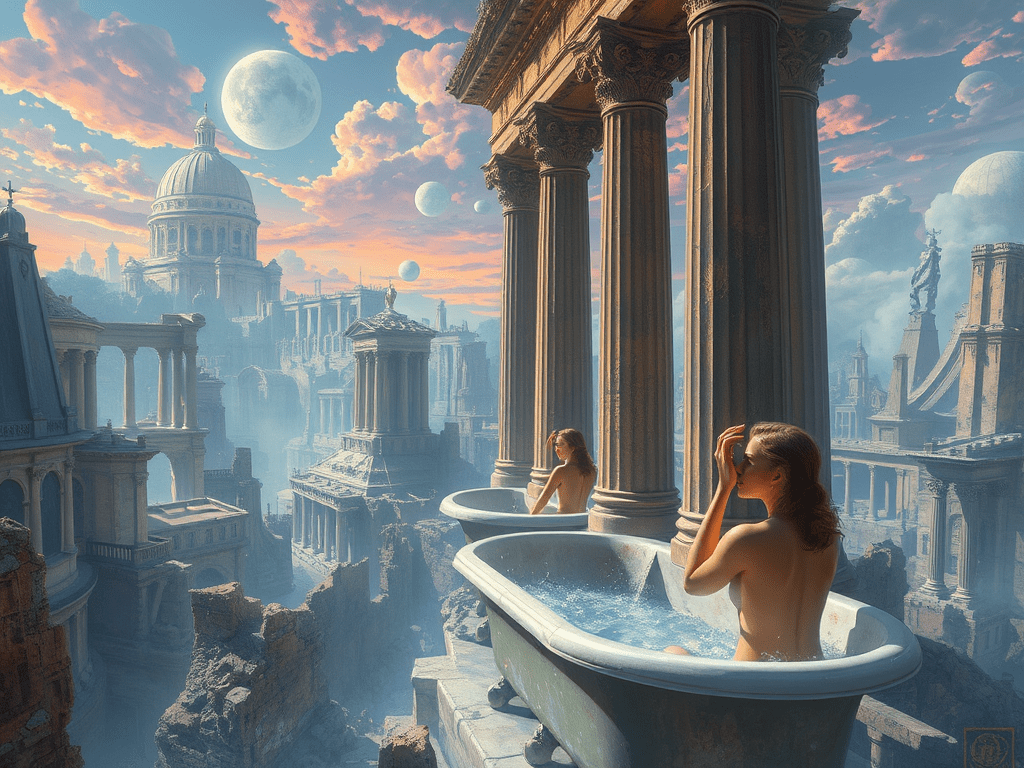

Invisible Cities

Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities is a skinny book that condenses the experience and idea of living and feeling cities in abstract and manifest ways. It has been a prized possession since I was a student even though I read it a long time ago and still read random chapters. I got hooked by the matter-of-fact, almost parable-like but incisive visions set ablaze in each chapter of the book, which unveils a different city as narrated in an imaginary conversation between Kublai Khan, the Tatar emperor, and Marco Polo, the traveler. Marco talks about the cities with such great tangents and flourish, leaving you gasping at the delightful insights.

The lyrical narrative of cities is replete with symbolisms and metaphors. These serve as the readers’ devices to begin their treatises on reality and fiction, memory and desire, and past and present. Calvino masterfully writes about the limitation of communication and power, ephemeral but universal cycles of urban living among the ruins and glory of concrete columns, cities as projections of human psyche, and the possibility of whims and greed as cogent sources of creativity. You could try and ponder over Calvino’s dispatches from the book on some of the real cities and their architects – the tunnel cities in China, Berlin, Turkey and those under Gaza and South Lebanon, Ghost city of Pripyat, Ukraine, and Fake cities in North Korea.

Calvino belongs to the OULIPO(Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle – Workshop of Potential Literature), a group of writers, logicians, and mathematicians whose primary objective is the systematic and formal innovation of constraints in the production and adaptation of literature (they also define themselves as rats who themselves build the labyrinth from which they will try to escape). The Oulipo believe that all literature is governed by constraints, be it a sonnet, a detective novel, or anything else. By formulating new constraints, the Oulipo is thus contributing to creating new forms of literature.Calvino’s fictional cities delve into the mind of each city that you and I have known or could have known from our personal view of the immediate outside world. The personal account of your life could exactly sound like someone else’. Or the kind of experience and people that you met at the first job that you had done in the city would sound agonizingly similar to someone else if you shift the time a little bit. There must always be someone who fought your fights, cried your cries, dreamt your dreams, and lived your life in some city that you think you lived and known for a lifetime.

For example, the invisible City of “Armilla has weathered earthquakes, catastrophes, corroded by termites, once deserted and re-inhabited. It cannot be called deserted since you are likely to glimpse a young woman, or many young women, slender, not tall of stature, luxuriating in the bathtubs or arching their backs under the showers suspended in the void, washing or drying or perfuming themselves, or combing their long hair at a mirror.”

—If on arriving at Trude I had not read the city’s name written in big letters, I would have thought I was landing at the same airport from which I had taken off. . . . “You can resume your flight whenever you like,” they said to me, “but you will arrive at another Trude, absolutely the same, detail by detail. The world is covered by a sole Trude which does not begin and does not end. Only the name of the airport changes.”

“Eutropia (a “trading city”) is made up of many cities, all but one of them empty, and its inhabitants periodically tire of their lives, their spouses, their work, and then move en masse to the next city, where they will have new mates, new houses, new jobs, new views from their windows, new friends, pastimes, and subjects of gossip. We learn further that, in spite of all this moving, nothing changes since, although different people are doing them, the same jobs are being done and, though new people are talking, the same things are being gossiped about.”

From their conversations which began with signs and sounds unintelligible to both, to perfecting each other’s language, to the numbness of understanding through silence, Marco Polo the traveler and Kublai Khan the Emperor have sailed through a lot of cities. Kublai asked Marco: “You, who go about exploring and who see signs, can tell me toward which of these futures the favoring winds are driving us.” Already the Great Khan was leafing through his atlas, over the maps of the cities that menace in nightmares and maledictions: Enoch, Babylong, Yahooland, Butua, Brave New World.

He continued: “It is all useless, if the last landing place can only be the infernal city, and it is there that, in ever-narrowing circles, the current is drawing us. “And Polo said: “The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become so part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, amid the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.”

I have had my fair share of cities. You leave a part of you every time you move on to a new destination, hoping you will find what you think you need! eventually, you might visit these cities at some point, hoping again to relive the life and time for a moment with a sense of detachment. Looking back I can see the trail I trod from the walkways in Cochin to Bangalore where the job hunters’ hopes, despair, and celebrations with friends were drenched in rum, to the long and sweltering bus trips to work in Chennai, to Chicago where everyone read something in the commuter trains and Fridays were an onslaught of adrenaline, to New York where you find countless people and cars travel all around you and yet you can listen to the tireless voice of a subway singer with his violin, to the laid back life in small town Pennsylvania and now in this aged, withering city of Philadelphia. -

Backyard Brawls

Imagine a backyard in a small town lost in Appalachia, where uncles, cousins, and friends from the neighborhood gather for Thanksgiving—or some other inopportune occasion. One of them—an uncle, tipsy and loud—starts ranting about a long-forgotten feud. A certain family member, he insists, isn’t grateful enough for his life or the family. He must be taught a lesson—now, and how! Thus, the customary brawl breaks out, ending as always: with one or two shotguns fired in random directions, a volley of aimless verbal violence, and a mess of broken furniture.

The ever-present mix of helplessness, poverty, and alcoholism—practically a permanent disability in town—seeps into people’s minds, corroding whatever remains of reason. Violence lurks in every corner, waiting for the slightest spark. Even those lucky enough to escape the gravitational pull of that world are never entirely free. J.D. Vance, against all odds, defied gravity—and found himself in the house of unlimited power.

Zelensky had spent years fighting an existential battle against a hard, dour, and ruthless dictator with limitless resources. But none of that prepared him for dinner at the Oval House, hosted by JD. As soon as the guest in army uniform took his seat, JD saw the setting morph into the familiar gray backyard from Appalachia where Uncle Trump needed a nudge and a reminder of how things ought to be done. It shouldn’t matter that JD and Rubio voted against the help for which Zelensky wasn’t “thankful enough”. The ungrateful visitor must be verbally put in his place. He should thank his stars that the brawl ended with just the denial of dinner and a summary send-off, not a sentence or broken bones.

Unfortunately, the Ukrainians could have done little to avoid invasion and outlast the medieval brute. Cowering before a dictator, ruing his misfortune ever since his tanks began exploding on the road to Kyiv—doesn’t inspire awe or respect. Enemies of democracy couldn’t believe their luck, while the rest stood paralyzed—too worried and confused to predict an uncertain future.

In their misguided zeal to cling to power, Democrats, liberals, and traditional Republicans ignored the crumbling foundation of freedom and decency. By allowing illiberal and aberrant elements to take center stage, they paved the way for dysfunctional folks from the backyard to seize the house of power.