Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities is a skinny book that condenses the experience and idea of living and feeling cities in abstract and manifest ways. It has been a prized possession since I was a student even though I read it a long time ago and still read random chapters. I got hooked by the matter-of-fact, almost parable-like but incisive visions set ablaze in each chapter of the book, which unveils a different city as narrated in an imaginary conversation between Kublai Khan, the Tatar emperor, and Marco Polo, the traveler. Marco talks about the cities with such great tangents and flourish, leaving you gasping at the delightful insights.

The lyrical narrative of cities is replete with symbolisms and metaphors. These serve as the readers’ devices to begin their treatises on reality and fiction, memory and desire, and past and present. Calvino masterfully writes about the limitation of communication and power, ephemeral but universal cycles of urban living among the ruins and glory of concrete columns, cities as projections of human psyche, and the possibility of whims and greed as cogent sources of creativity. You could try and ponder over Calvino’s dispatches from the book on some of the real cities and their architects – the tunnel cities in China, Berlin, Turkey and those under Gaza and South Lebanon, Ghost city of Pripyat, Ukraine, and Fake cities in North Korea.

Calvino belongs to the OULIPO(Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle – Workshop of Potential Literature), a group of writers, logicians, and mathematicians whose primary objective is the systematic and formal innovation of constraints in the production and adaptation of literature (they also define themselves as rats who themselves build the labyrinth from which they will try to escape). The Oulipo believe that all literature is governed by constraints, be it a sonnet, a detective novel, or anything else. By formulating new constraints, the Oulipo is thus contributing to creating new forms of literature.

Calvino’s fictional cities delve into the mind of each city that you and I have known or could have known from our personal view of the immediate outside world. The personal account of your life could exactly sound like someone else’. Or the kind of experience and people that you met at the first job that you had done in the city would sound agonizingly similar to someone else if you shift the time a little bit. There must always be someone who fought your fights, cried your cries, dreamt your dreams, and lived your life in some city that you think you lived and known for a lifetime.

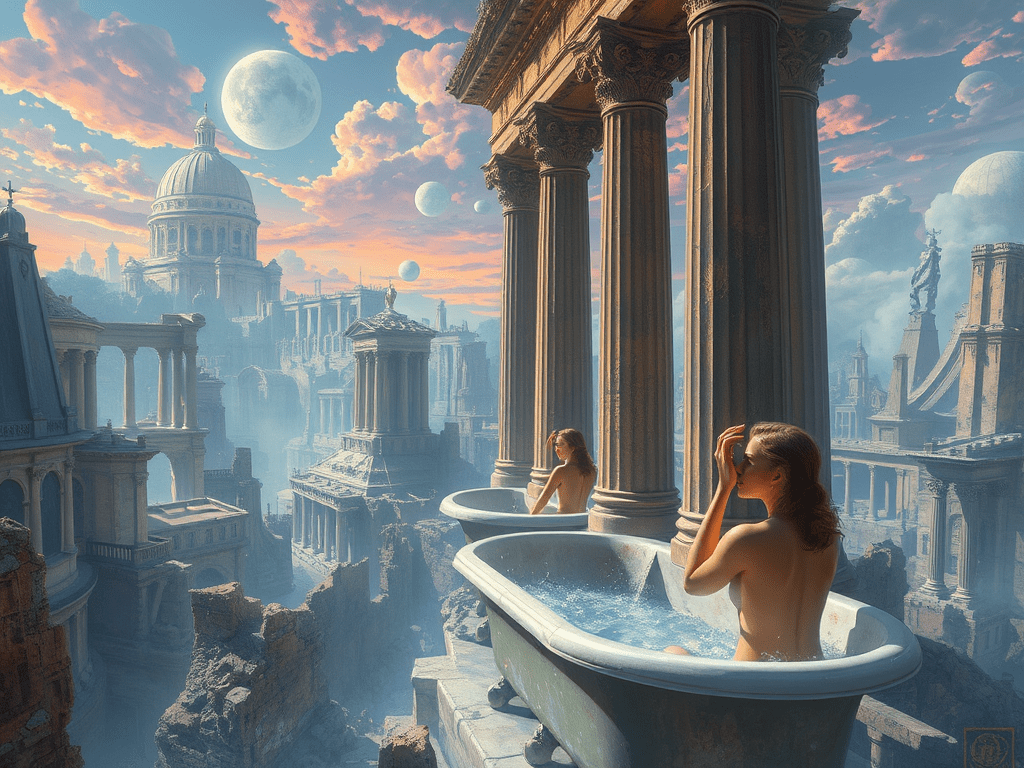

For example, the invisible City of “Armilla has weathered earthquakes, catastrophes, corroded by termites, once deserted and re-inhabited. It cannot be called deserted since you are likely to glimpse a young woman, or many young women, slender, not tall of stature, luxuriating in the bathtubs or arching their backs under the showers suspended in the void, washing or drying or perfuming themselves, or combing their long hair at a mirror.”

—If on arriving at Trude I had not read the city’s name written in big letters, I would have thought I was landing at the same airport from which I had taken off. . . . “You can resume your flight whenever you like,” they said to me, “but you will arrive at another Trude, absolutely the same, detail by detail. The world is covered by a sole Trude which does not begin and does not end. Only the name of the airport changes.”

“Eutropia (a “trading city”) is made up of many cities, all but one of them empty, and its inhabitants periodically tire of their lives, their spouses, their work, and then move en masse to the next city, where they will have new mates, new houses, new jobs, new views from their windows, new friends, pastimes, and subjects of gossip. We learn further that, in spite of all this moving, nothing changes since, although different people are doing them, the same jobs are being done and, though new people are talking, the same things are being gossiped about.”

From their conversations which began with signs and sounds unintelligible to both, to perfecting each other’s language, to the numbness of understanding through silence, Marco Polo the traveler and Kublai Khan the Emperor have sailed through a lot of cities. Kublai asked Marco: “You, who go about exploring and who see signs, can tell me toward which of these futures the favoring winds are driving us.” Already the Great Khan was leafing through his atlas, over the maps of the cities that menace in nightmares and maledictions: Enoch, Babylong, Yahooland, Butua, Brave New World.

He continued: “It is all useless, if the last landing place can only be the infernal city, and it is there that, in ever-narrowing circles, the current is drawing us. “And Polo said: “The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become so part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, amid the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.”

I have had my fair share of cities. You leave a part of you every time you move on to a new destination, hoping you will find what you think you need! eventually, you might visit these cities at some point, hoping again to relive the life and time for a moment with a sense of detachment. Looking back I can see the trail I trod from the walkways in Cochin to Bangalore where the job hunters’ hopes, despair, and celebrations with friends were drenched in rum, to the long and sweltering bus trips to work in Chennai, to Chicago where everyone read something in the commuter trains and Fridays were an onslaught of adrenaline, to New York where you find countless people and cars travel all around you and yet you can listen to the tireless voice of a subway singer with his violin, to the laid back life in small town Pennsylvania and now in this aged, withering city of Philadelphia.